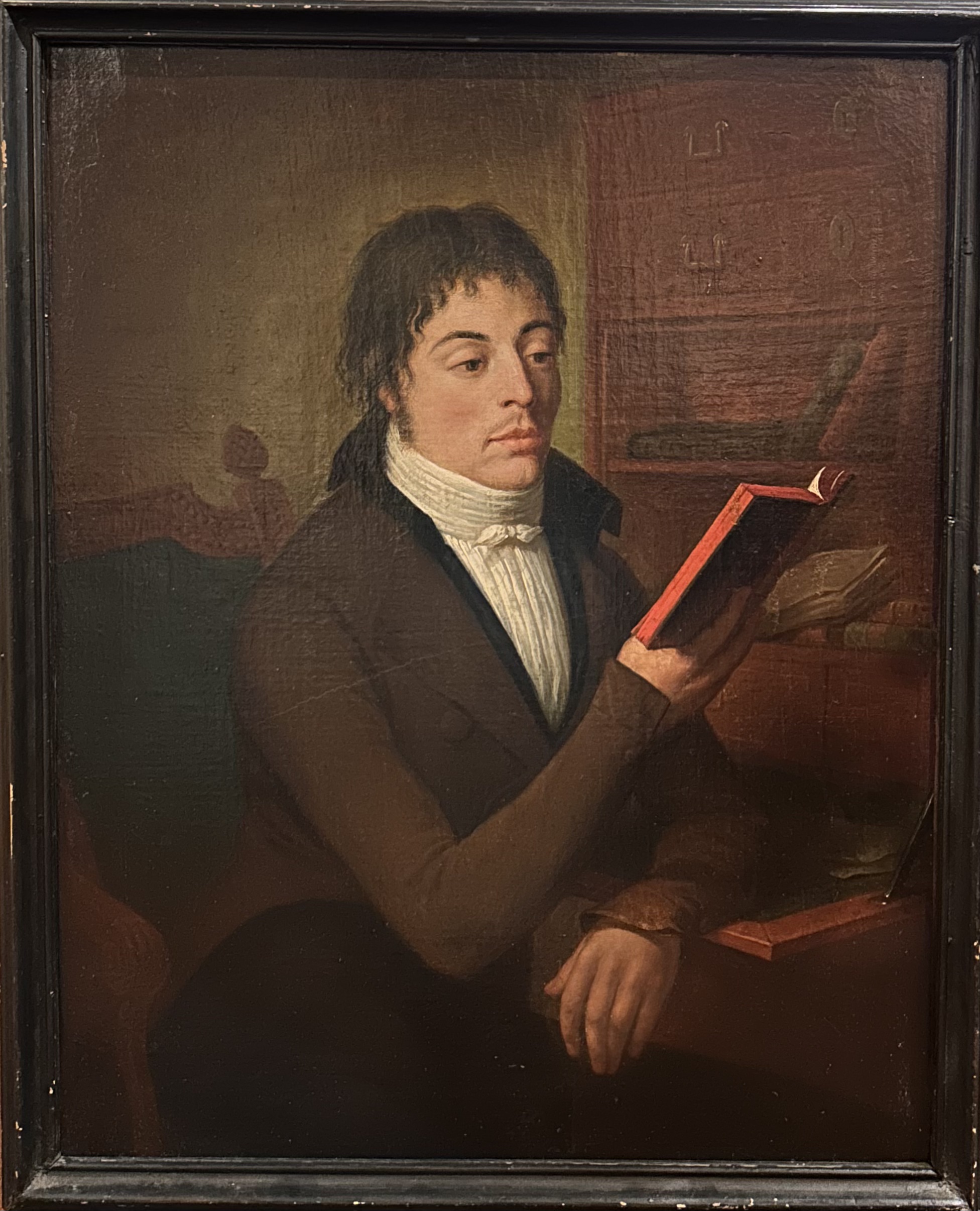

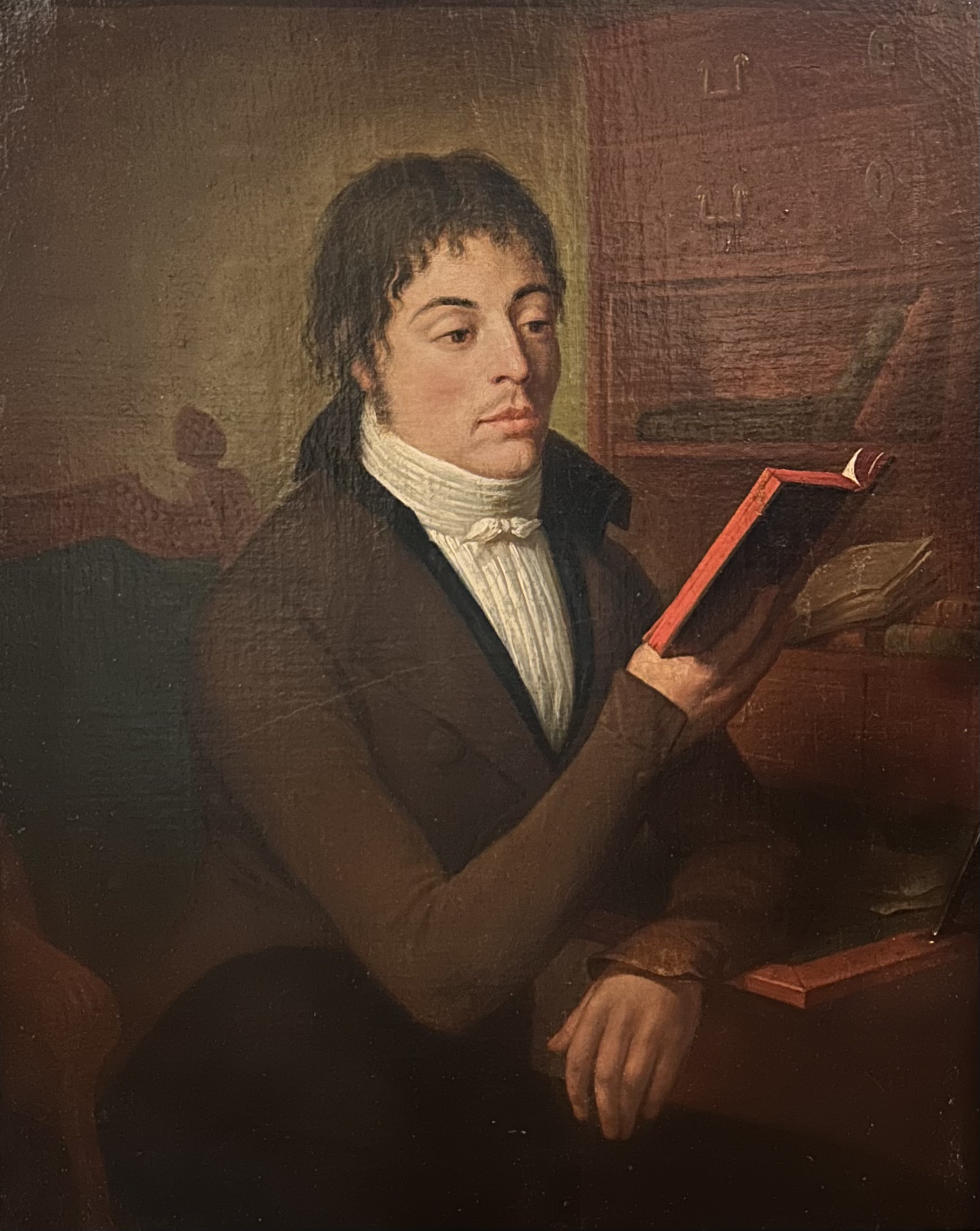

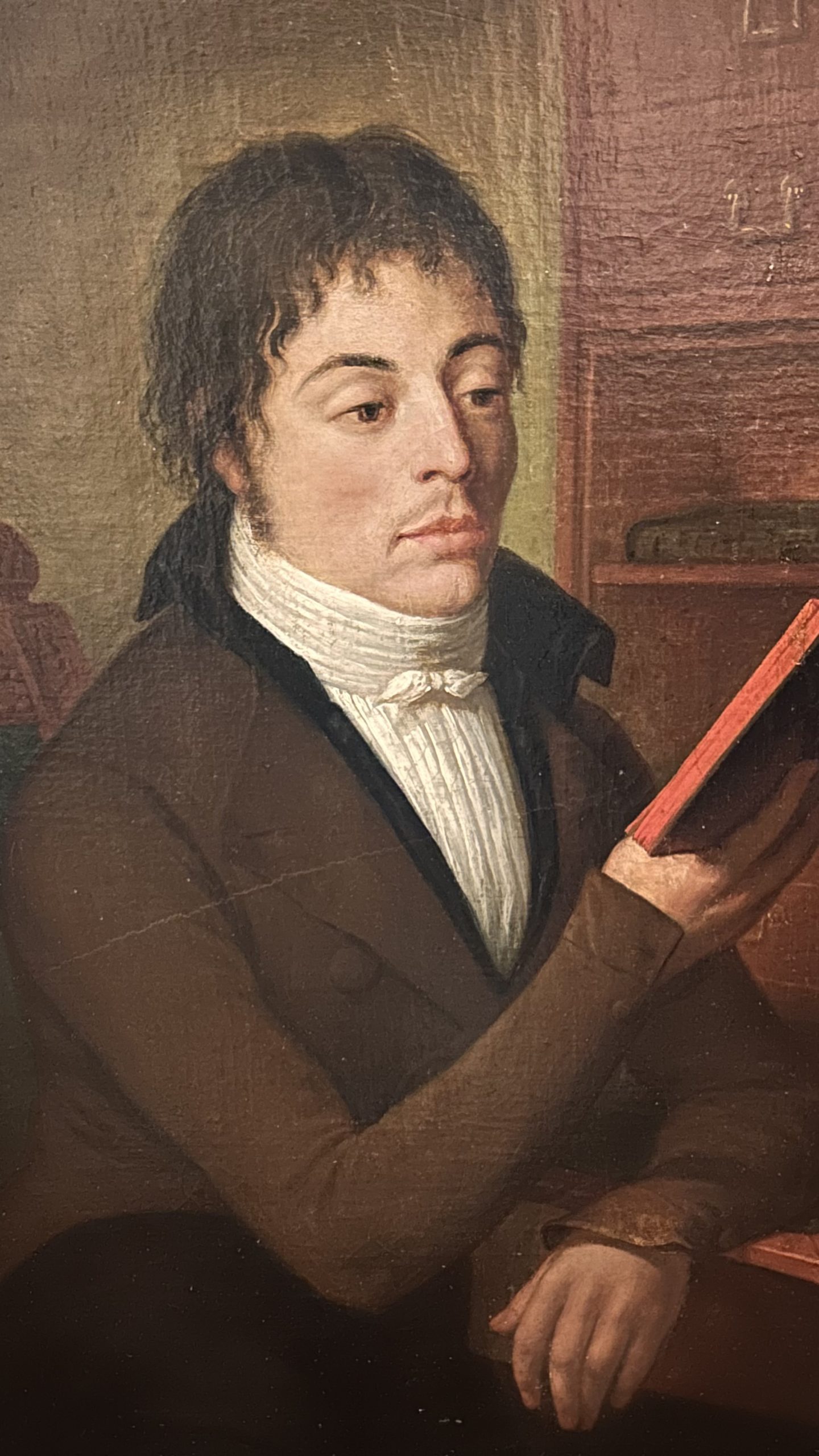

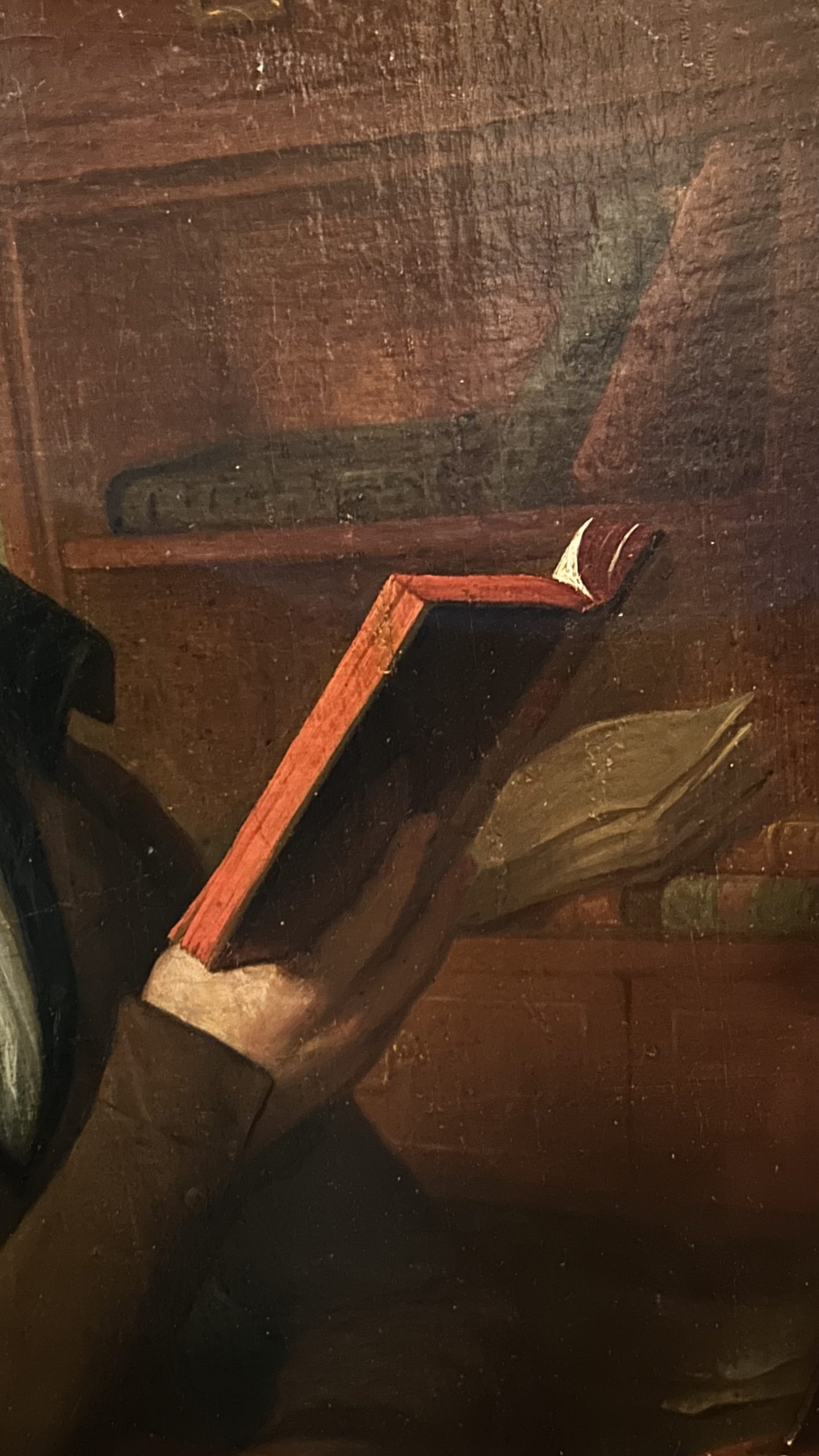

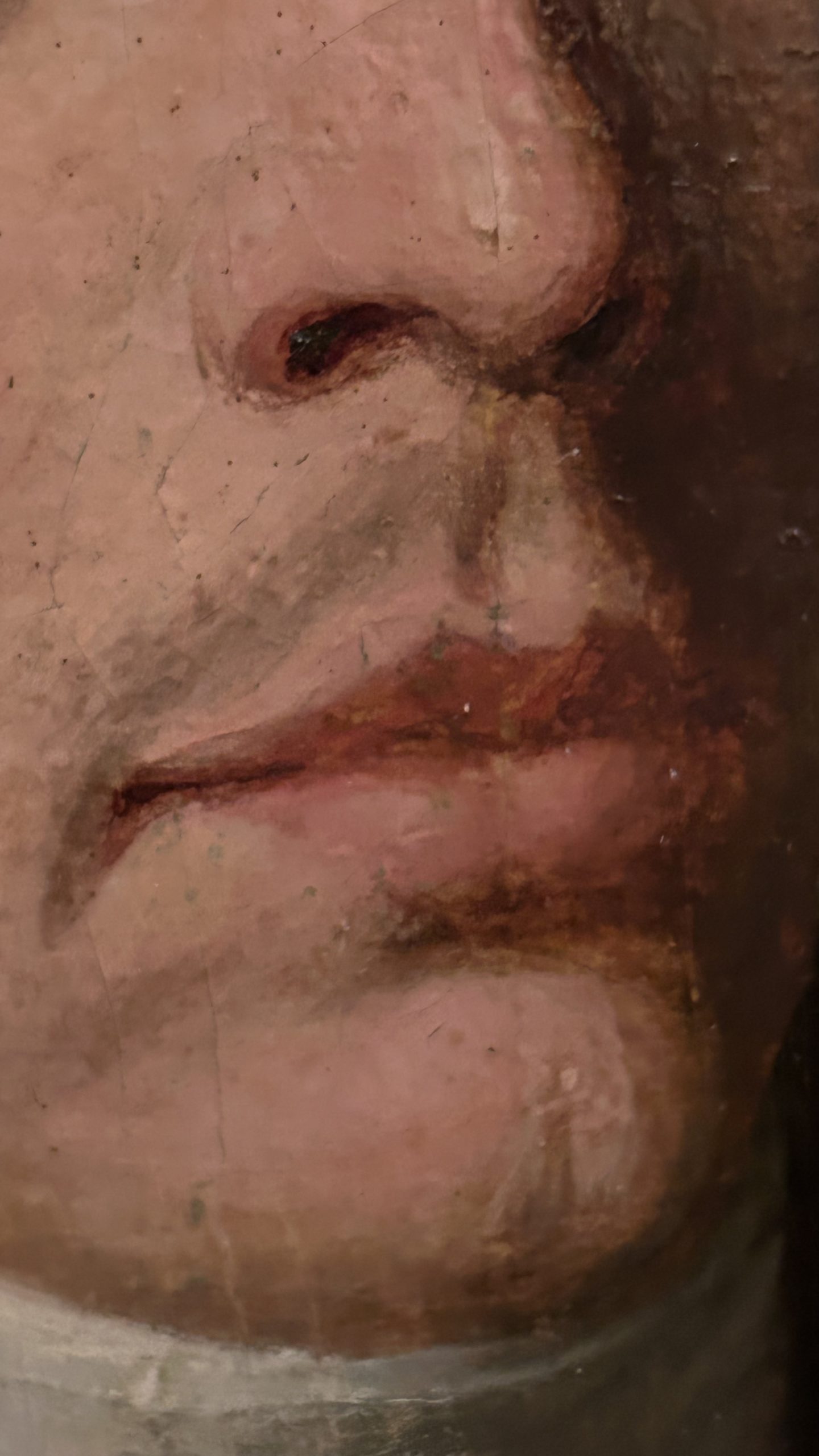

Oil on canvas, portrait of a young man reading in front of a secretary, one arm resting on the flap, signed by Dominique Doncre lower right and dated 1802. Several of his works are currently (January 2025) exhibited at the Marmottan museum on the occasion of the Trompe-l’oeil exhibition and many paintings are at the Arras Museum of Fine Arts, including his self-portrait. Born in Zegerscappel on March 28, 1743, Dominique Doncre is a good example of an artist attached to his province. He settled in Arras in 1770 where he spent most of his career until his death in 1820. Dominique Doncre (1743-1820) dominated the artistic life of Arras at the end of the 18th century. In 1794 Doncre also presided over the creation of the Arras museum, of which he was the first curator, participating in the selection of works. The District Directory had charged him, on March 4, 1793, with valuing the works of art coming from the property seized from emigrants; on June 20 he had to make a choice among the paintings and various works which were at the Saint-Vaast abbey.

The Pas-de-Calais departmental archives have preserved the inventories drawn up by Doncre. The latter testify to his strong taste for Flemish and Dutch art, a direct echo of his initial training, probably in Antwerp. His virtuosity in the art of trompe l’oeil and grisaille has sometimes led to the writing that the artist “had worked in Envers with Martin Geeraerts” (1707-1791). Certainly, the latter gave lessons at the Envers academy from 1741, but no document confirms the hypothesis that Doncre was his student.

“After having first tried to form a clientele in Saint-Omer, the artist was not long in joining the town of Arras, where a drawing school had just opened at the initiative of the States of Artois. The capital of the province seems to have immediately reserved for him a welcome that responded to his aspirations: in 1772 Doncre took the oath of bourgeoisie, before being admitted to the brotherhood of Saint Luc. Thanks to his introduction into wealthy circles of the city, he then produced important grisailles and wall decorations for various private mansions including that of the governor of Artois, the Duke of Lévis.

Until 1789, he mainly found his sponsors “in the local robed nobility and more particularly in the circles of the Council of Artois, among the recent nobility from local merchants and businessmen. From 1780-1785, the young Boilly went to Arras, called by Monsieur de Gonzié, in order to produce several portraits. “Did he take advantage of Doncre’s relatively long absences at this time to build up a local clientele? However, this did not hold him back when he wanted to move to Paris. Note, however, that one of Doncre’s best trompe-l’oeil dates back to 1785, which according to tradition gave lessons to Boilly. “Needed to adapt to political circumstances, Doncre was able to continue his career as a local portraitist under the Revolution, the Empire and the Restoration. However, if the portrait constituted the major part of his work, “religious painting, decorative composition, genre scene then form more of the remaining shots” of his work. Without direct descendants, Doncre’s works were dispersed shortly after his death and the artist seems to have been forgotten. In 1853 “the Arras Academy put into competition a biography of Dominique Doncre with appreciation of the main works he produced”. In 1868, Constant Le Gentil, a magistrate, published a biographical work Dominique Doncre (1743-1820); this last book was enriched in 1902 by an article by the scholar Victor Advielle.

Doncre provided the face of Arras society at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. The cover shows the trompe l’oeil from the Arras museum, painted in 1785, one of his best works. As Anne-Marie Lecoq writes, “the besicles with broken glass and the worm-eaten frame of Dominique Doncre’s letter rack are also part of the processes used in trompe l’oeil exercises. But as opposed to the idea of poverty and ruin that they give rise to in the mind of the spectator, Doncre slipped his own image into the letter rack, that of an elegant and proud man, accompanied by the noble motto: “Ego sum Pictor”, “And I am a painter.” So much so that the viewer no longer knows how to imagine the world around the painting, nor the social status of the owner of the letter rack.” (Pierre Georget and Anne Marie Lecoq, Painting in painting, Adam Biro edition, 1987, p.249).

Height: 86cm

Width: 70cm